Wherever monuments were built in the ancient world, wherever man raised his eyes to the heavens and built on earth, a surveyor was there. Whether the circles of Stonehenge, the pyramids of Egypt or South America, the ancient temples of Greece and Rome, all were laid out with specific relationships that codified the relationship between the people, their government, and their deity.

The earliest recorded surveys were conducted by the ancient Egyptians. Famous for their monuments, they are perhaps best known now for the only remaining structure of the original “Seven wonders of the world,” the Great Pyramid of Giza. For 3,800 years the tallest structure in the world, it’s almost exact north-south orientation and precise geometry are a testament to the surveyors who laid out the plan using little more than knotted ropes and plumb bobs. But the Egyptians used surveying for more than establishing their monuments, there are 4,000 year old clay tablets establishing property boundaries for ownership and sale of land. These provided the basis for the Egyptian economy, for agriculture, and for trade throughout the region. As the Nile river flooded each year, washing away boundary markers, surveying was an annual necessity for the continuance of a civil society.

As Greek civilization grew they looked to Egypt, as the Romans in turn looked to Greece. Around 522 B.C.E. it was the engineer Eupalinos who dug the underground aqueduct that bears his name on the island of Samos. Over a thousand meters in length, the tunnel was dug through solid rock from both ends simultaneously, tunneling through a mountain to provide an uninterruptible water source for the town. Without exact measurements the two tunnels may have never met, but Eupalinos managed the feat with tremendous accuracy, using nothing more than Geometry and a perhaps a forerunner to the surveying instrument invented by the Greeks, the Dioptra. A disc leveled by screws and inscribed with angles, the dioptra could be used to determine the angle between two distant objects from a fixed point.

The Romans adapted the Dioptra, and well as a Mesopotamian tool they called the Groma. Together with spirit levels and odometers, these tools provided surveyors and engineers with all the information necessary to lay out colonies, build cities and monuments, aqueducts and roads, some of which are still in use today. At it’s height, the Roman water system used eleven separate aqueducts spanning almost 400 kilometers to bring over one million cubic meters of clean water into the city every day.

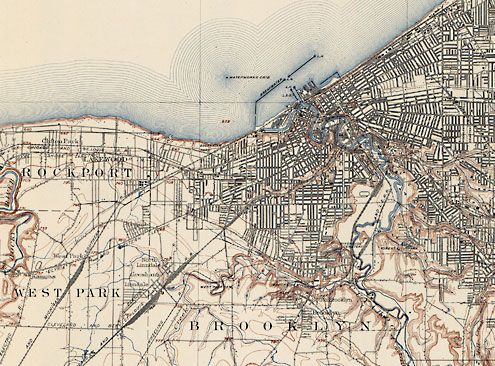

It wasn’t until the 16th century that the Theodolite came into use. A precision instrument for measuring angles in both the horizontal and vertical planes, it has survived into the modern era with continual upgrades. In the United States, George Washington, Daniel Boone and Lewis and Clark are but a few of the surveyors whose use of the theodolite had profound impacts on the young nation’s history. In civil engineering circles, Mt. Rushmore is often jokingly referred to as “three surveyors and some other guy,” though there is a move afoot to consider Theodore Roosevelt a surveyor as well. His famous 1913-1914 map-making expedition to Brazil resulted in a river there being named after him (Rio Roosevelt, sometimes known as Rio Teodoro) and almost cost him his life.

Modern theodolites now come equipped with infra-red based measuring devices, software, and may even be remote controlled. Though the technology has changed, the goal remains the same as it has been throughout land surveying history: to quantify the unknown.